Mind precedes all phenomena.

Mind is their chief; they are all mind-made.

If with impure mind a person speaks, or acts,

Suffering follows him like a wheel that follows the foot of an ox.

Mind precedes all phenomena.

Mind is their chief; they are all mind-made.

If with pure mind a person speaks, or acts,

Happiness follows him like his never-departing shadow. (Dhp 1-2)

About this site

home > about

Buddhism began with the Buddha, a towering figure who lived some hundred generations ago, taught for forty-five years, during which he gained a huge following of ascetics and householders, kings, merchants, craftspeople, and paupers. As long as Buddhism had not wandered too far from the person of the Buddha and his immediate disciples, its sophisticated teachings and practices might have remained, at least among the adepts, close to pristine. This was the period of early Buddhism. Over the centuries and millennia, his influence continued to spread far and wide, into diverse lands, blending with dissimilar cultures, to become the first World Religion. Even while enveloped in the demands of a distinct folk culture in each new land, it has proved remarkably robust in fulfilling its early mission. But now it has encountered modernity.

The Buddha’s quest began with the problematic nature of the human condition. Why do we have to lose, one by one, everything and everybody who is dear to us? Why do we endure so much physical and emotional pain, sickness, old age an death? Even on a “good” day, why do we enjoy pleasure of the senses, but then find that they lack meaning? Why is satisfaction so elusive, even when we achieve our goals? Why does life seem like an endless series of broken promises? Why do we remain stuck in this world aflame in suffering all around, wanting out, but helplessly caught in sustaining that suffering for ourselves and others?

Almost uniquely, the Buddha’s answer to these questions did not appeal to the efficacy of a higher power, but rather recognized that these were human problems with human causes that arise in human minds, and that they therefore might have human solutions. The Buddha’s solution relies on the development and cultivation of our innate potential as creatures of virtue and wisdom, all too often dismissed in our coexisting monkey minds’ scrambling for personal advantage. Buddhism is not an easy-answer religion: improving our virtue and our wisdom requires living according to high standards, and perfecting virtue and wisdom requires a commitment to a life of intense and relentless practice. However, successfully undertaken, Buddhist practice can be a guarantor of personal flourishing in a life of fulfillment and meaning. The Dhamma is our guide for living a Buddhist life. It stands out in its enormous sophistication, and its emphasis on developing mind rather than on improving external conditions beyond our needs. The Dhamma provides a program for the wholehearted practitioner whereby the mind is tuned, honed, sharpened, tempered, straightened, turned, and distilled into an instrument of virtue and of wisdom. The Dhamma is itself among the greatest products of the human mind, skillfully articulated by the Buddha.

Cintita.org has been developed with culturally modern people in mind who want to explore, and perhaps devote themselves to Buddhism as it was understood by the Buddha and his early disciples. As a western Buddhist monk, former cognitive scientist, current Dhamma and meditation teacher, and scholar of early Buddhism, I offer in these pages material to read, talks to hear, as well as personal guidance for the modern aspirant to put into practice. I hope to demonstrate that Early Buddhism, properly interpreted, provides a basis for fashioning oneself into something rare in our modern culture, into a person of virtue and wisdom, so that the modern world might become a gentler and saner place for us all. Having myself navigated the treacherous waters that separate the most ancient Buddhist worldview from modern notions, I think of myself as a bridge (or at least a ferry boat) for the modern student. I offer early Buddhism for modern Buddhists.

What is early Buddhism?

The Buddha-to-be left his family’s lavish lifestyle as a young man to embark on a spiritual quest as a homeless ascetic. At an age generally reckoned as thirty-five, he achieved awakening. After that, he taught Dhamma until passed away at a ripe old age of eighty, by which time his disciples numbered in the many thousands, many of whom had achieved his awakening. During the first decades or centuries after the Buddha, Buddha’s teachings were preserved through oral recitation, and compiled into various collections to form a voluminous corpus that we now call the “early Buddhist texts” (EBT).

There is still some uncertainty about which of these texts represent the words of the Buddha, and which might be of later composition, but a strong case can be made for their overall doctrinal integrity. These early teachings evolved variously in different regions of the Buddhist world to produce various traditional sects and schools of Buddhism, as they added, subtracted or reinterpreted the EBT. However, the EBT themselves were preserved, relatively faithfully, alongside newly composed scriptures in many of these schools. What was to become the most complete version of the EBT as a whole was transmitted to Sri Lanka in the third century BC in the Pali language, and is preserved in Pali today in the Theravada tradition of Southern Asia. Equivalent texts with diverse histories of transmission are preserved in the Chinese, and in other languages.

Later scriptural traditions that developed throughout the Buddhist world largely eclipsed the EBT in most places, but almost invariably claimed to represent exactly what the Buddha taught (no modern school, including Theravada, actually does). With modern scholarship can we have begun to isolate the EBT from what came later. This has resulted in a recent surge of interest in these early texts, since they come closest to carrying the full authority of the Buddha, and with that a higher expectation of coherence and efficacy. Unfortunately, reaching a consensus about a proper comprehensive interpretation of what these often obscure ancient texts actually mean continues to be elusive. This is at the center of my own scholarly activity.

Who are modern Buddhists?

Modern Buddhists often complain that Asian Buddhism is mired in cultural baggage, and that only in the west can we understand it for what it is. Buddhism has doubtlessly acquired a cultural overlay—a “folk Buddhism”—in every land it has established itself. However, Asian cultures have had centuries to iron out inconsistencies with core Buddhist principles, which continue to be upheld by the adepts, generally the monastics. A strength of Buddhism, and perhaps the basis of its history of projecting itself successfully into new cultures, is its tolerance as it blends with local folk traditions. Asian folk Buddhism is irksome primarily to those carrying modern, or western cultural presuppositions, but understanding local folk Buddhisms is also not necessary for an understanding of core principles. I daresay that it is modern cultural baggage that merits caution. Often it is so thick that what many modern teachers offer is, unknown to themselved, rooted much more in western religious and intellectual history than in Asian, yet presented in Buddhist guise. Modern misunderstandings of what is, and is not Dhamma, has itself even become a fruitful area of modern scholarly research.

Modern Buddhists now exist throughout the world. Modernity tends (particularly in the States) to be materialistic, hyper-individualistic, and competitive, and it relishes a lifestyle rich in choices and distractions. These qualities make Dhamma and its practice enormously challenging for modern people, as they try to find a category for it in familiar terms: Religion? Self help? Psychotherapy? A meditation technique? Philosophy? Science of mind? A way of life? For many, it is a shopping experience: “Got my Buddha.” “Got my ergonomic meditation cushion.” “Got a Buddha-quote on my t-shirt.” The meditation timer often goes unused, like so much home gym equipment.

My assessment is that Buddhism can play a profoundly beneficial role as a corrective at those points in which modern culture is most dysfunctional, which are the points at which it is the greatest challenge for modern people. My advice is to let Buddhism be Buddhism by withholding our modern presuppositions of what it should be. Nonetheless, you will find and appreciate that the Dhamma has a solid natural basis in the workings of the human mind, and that Buddhist practice is invariably purposeful and practical (even when the first impression seems otherwise). You may find it reassuring that the early Dhamma is overtly critical of blind faith, and is, in fact, likely to undermine the unquestioned presumptions all of us already carry before entering Buddhist practice. Moderns often appreciate the deep skepticism inherent in early Buddhism, even with regard to its own teachings. Great open-mindedness is a boon for the successful Buddhist student-practitioner. The largely “come and see” empirical nature of Dhamma. often aligns well with modern sensibilities.

Who am I?

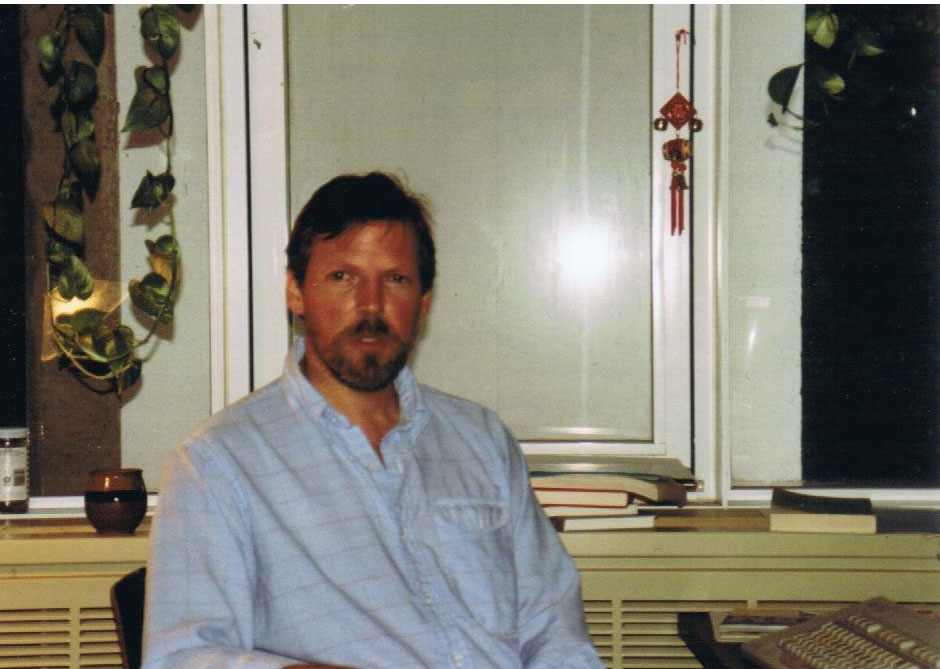

Born a boomer in San Francisco, a former academic in cognitive science, I am now a simple monk with a laptop. The world at large calls me “BC.” Formal students call me “Bhante.”

I earned a Ph.D. at the University of California at San Diego in theoretical linguistics, and then an MS in computer science in Kansas in order to become actually employable. I got married and began raising a family about this time. I became a professor of computer science at Illinois State University, where I taught programming languages and artificial intelligence. By this time I identified myself with “cognitive science” as a whole, which at that time was a burgeoning new field as scholars in linguistics, psychology, artificial intelligence, brain science, and philosophies of mind and language realized they were working on a lot of the same problems. I left academia to do research and development in artificial intelligence at a corporate think-tank in Austin, TX for a few years, but began to realize the potential harm that this kind of R&D might bring to the world. My background in cognitive science would shape my understanding of the Buddha’s teachings (strongly psychologically based) in the years to come.

I caught the Buddha bug in the late nineties, became a devout Soto Zen practitioner, and was a founding member of the Austin Zen Center. I had already been a meditator in a non-Buddhist tradition since 1980. In 2001 decided to abandon my high-tech career in order to devote myself to the more beneficial pursuit of Buddhist study and practice. I lived for over a year at the Tassajara Zen Mountain Monastery in California, then returned to Austin to ordain as a priest in 2003. There I trained, studied, and taught meditation and Buddhism at the Zen Center. I was also invited to teach in Texas prisons, where I found inmates who were as eager for, and capable of Buddhist teaching as my best students on the outside.

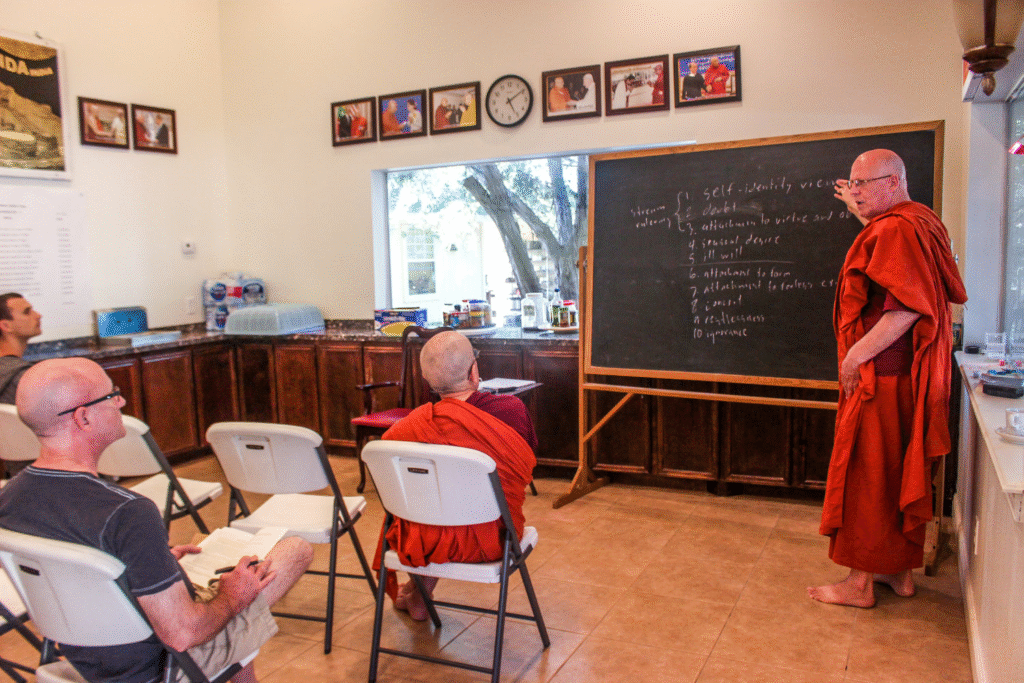

I admire Japanese Zen to this day, but discovered that the traditional monastic order—the Sangha founded by the Buddha so that the Dhamma might burn most brightly—had all but disappeared (uniquely among Buddhist nations) in Japan. Having befriended four Burmese monks living in the forest in a house-trailer/monastery, I was invited to accompany the abbot to Myanmar in 2009. There I changed into the maroon robes of a Theravada monk, received the Pali name Cintita (‘good thinker’), and lived for thirteen months. For almost two months I was one of 300 monks practicing intensely at the main Pa Auk meditation center.

Returning to the States, I was surprised to find that the once primitive Burmese monastery in Austin had become a construction site; it has since expanded into a very active, large residential meditation center and library. My primary residence has bounced between Texas and Minnesota, where a smaller sister monastery has developed in the Lake Country. I now reside almost full-time in Minnesota with four Burmese monks

Over the years I have been engaged in study and practice, teaching, scholarship, and writing centered around early Buddhism. I teach primarily to westerners, and try better to understand the remarkable sophisticated early teachings of the Buddha with a scholar’s eye, and a practitioner’s determination. The focus of my research is attaining a proper interpretation of what these ancient texts say. Over time I have developed a somewhat unique methodology for evaluating proposed interpretations, employing rigorous and expansive standards, including consistency with what we know independently about human cognition, often reaching contrasting conclusions from other scholars. This site is intended to highlight this perspective.

John Dinsmore, BC’s former incarnation

What you will find at cintita.org

The top half of this site is an art gallery, photographs from a unique collection of recent replicas of ancient statuary from different times and places in Asia, displayed along with inspiring passages from the early texts. The collection of twenty-four two-foot Buddha figures is found physically in the Shwezigon Pagoda at the Sitagu Buddha Vihara in Austin, TX, and were created on site by a team of Burmese artisans under the direction of traditional architect Tampawaddy U Win Maung. The link “Credits” in the footer below provides information on this collection. , We’ve attempted to provide a quiet space for exploring the other materials offered, like walking through an art gallery, In lieu of the attention-grabbing dynamics found in more cutting-edge web sites.

The other materials provide for the student/practitioner a guide for study and practice according to the early texts. This site highlights my own work—books, essays, and talks—along with attention to important EBT-related work by other authors consistent with the distinct method of scholarship I represent, which brings unity to the body of this work. The method is based on the perspective of the Dhamma as a holistic, coherent, systematic, and functional whole, consistent with what we know independently about human cognition.

Clicking “Study & Practice” accesses a curriculum for the dedicated student-practitioner in living a contemplative Buddhist life, understanding the fine points of Dhamma, navigating the noble eightfold path, and making steady progress in shaping a life rooted in virtue and wisdom. “Resources” provides direct access to my books, essays and talks, as well as recommended readings of other authors relevant to the study, practice, and scholarship of early Buddhism. All of my writings can be downloaded as a pdf, and hard copies my books can be ordered by those who like to flip through physical pages.

Click on “What’s New?” for access to more dynamic and interactive content. Among these are upcoming events, announcements and opportunities to follow or participate in ongoing discussions. There is a form through which you can pose Dhammic questions to me to open up a new thread in the blog. You can subscribe to discussions/blog in the footer below. Most of my live talks and classes are accessible through Zoom. You can also communicate with me directly for individual advice or discussion.

I hope this site will prove valuable in your life of practice in toward awakening.

Bhikkhu Cintita

September, 2025