Anne:

Can you describe in writing one of your most powerful experiences during meditation?

BC:

There is a tendency for modern practitioners to seek after dramatic, unanticipated, immediately life-altering experiences, to which they can attribute either awakening itself, a glimpse of awakening, or a less defined but nonetheless “mystical” experience. Some practitioners are obsessed with achieving such experiences. That might be what you are expecting me to have had, Anne. Seeking such experiences is craving, and certainly detrimental to practice. Accordingly, I try to discourage attributing too much importance to the wonder of such experiences. Though they will occur, the Buddha seems to have had little no or interest in the drama of such experiences, while giving attention to the growing sense of well-being that comes with successful practice to surpass mundane pleasure. We do not practice in order to have dramatic experiences, we practice in order to develop wisdom (as a support for virtue). In the process, however, we do come to see the world in radically different ways. Sometimes we cannot help but be astonished by what we see.

The experiences I’m referring to are sudden moments of insight associated with wisdom contemplation, in which something that was previously unclear becomes clear. Within the early Buddhist context, they occur particularly in Dhamma investigation (satipaṭṭhāna, vipassanā) within a meditative state (jhāna or samādhi). My book Rethinking Satipaṭṭhāna describes the mechanics of this practice, including what I am about to relate. Outside of the Buddhist context, insight experiences can also arise spontaneously, I suspect especially in children, where they can be disorienting and frightening in the absence of any preparation. In any case, they come suddenly, like a spark but occasionally like a lightning strike. They seem to bubble up from the unconscious mind, then make us want to shout, “Aha!” “Aha” experiences also come with with a conviction, almost a certainty, that one has seen into some deep truth.

However, the insight experience is typically at best poorly explained in conceptual terms. It is a product of intuition. Concepts generally do not do justice to the experience itself. Tejaniya Sayadaw, a Burmese meditation teacher, gives an example of an insight he once had as a meditation student. The best he could describe it conceptually was, “You can smell only with the nose.” Excited, he told other monks about this great insight, but they all laughed at him. He finally went to his teacher, who acknowledged the depth of this insight, but advised, “When you have an insight, don’t tell the other monks about it. They will think you are crazy.”

Common broad themes in these experiences are impermanence, non-self, the falling away of the distinction between subjective and objective experience, the nature and depth of suffering, and the mental constructedness of what we presume to be an independent reality“ out there.” The Buddha takes great pains to prime us for insights into such realms through his various Dhamma teachings. Being bound to language, he does this in conceptual terms. Many teachers and scholars accordingly take these conceptual teachings as philosophy, valuable in themselves. In fact, the Buddha’s concern seems to be limited to inducing the practitioner to be able to experience these teachings directly and non-conceptually. He expresses this achievement as “dwelling, having touched X with the body.” We do this through contemplation (in jhāna!) and discovering what the Buddha is talking about in our own experience, making it our own. Aha!

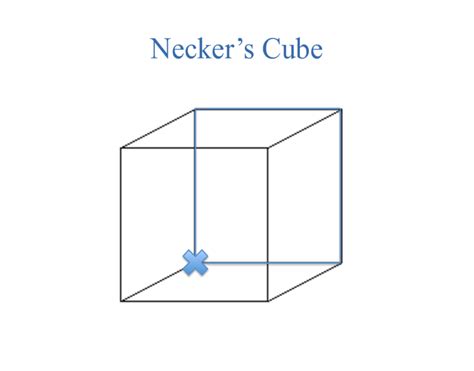

The closest simple and readily available analogy I’ve found in the mundane world is “Magic Eye” images, 2D patterns that when stared at suddenly (aha) reveal content that appears in 3D. I recommend that beginning practitioners play around with these (I’ve acquired a couple of books of such images for both our Austin and Minnesota libraries). A similar, even simpler effect is found in staring at a Neker’s cube:

Is the marked corner the closest to you, or the furthest from you? Once the mind has snapped into one interpretation, most people have difficulty snapping into the alternative interpretation. Discovering the alternative is then bound to produce an “aha” experience. One would think that the more firmly the mind is fixed on one interpretation, the more dramatic the discovery of the other will be. One might furthermore even conclude that the more open-minded one is, the more astonishing their insight experiences will be, if and when they eventually do occur.

One of my favorite wisdom practices is contemplation of the five aggregates, a teaching that leads to insight into the inseparability of mind from the objective, independent world “out there.” Effectively, it teaches the constructedness of reality. (Modern quantum physics seems to have become a precisely focused continuation of this exercise, beginning with the split beam experiment.) Once over twenty years ago I was sitting zazen many hours each day at Tassajara Zen Mountain Monastery in the California coastal mountains, where I lived for almost a year and a half. One is unlikely to learn the five aggregates in Zen, since one is given only vague ideas of what to look for in meditation, most importantly “emptiness” and “non-duality,” with little explanation. Zen takes pride in being a tradition “beyond words and letters,” which in my experience seems to have the effect that insights are few and far between, but it is a whopper if and when one happens to occur.

I must have had a very fixed idea at this time about the reality of an objective, independent world “out there,” for on this occasion something seemed to snap. I left the meditation hall and felt the world had shifted. I looked up at the tall mountains all around and saw clearly that I was in them and they were in me. There was no separation. I took a walk up the hill up to Suzuki Roshi’s burial sight and spent some time dwelling there in what I had touched. Then suddenly, after about 4 or 5 hours, I snapped back, and couldn’t recover my new interpretation of the world, only a vivid memory of it. I knew I should label the experience “non-duality,” but the label seemed meaningless in view the depth of the experience itself. It was only years later, when I was grounded in the Buddha’s teachings, that I could understand the various experiential facets of this little drama, and even begin explain it conceptually, to the satisfaction of philosophers, but inadequately from the perspective of practitioners. If I had started with the Buddha’s more detailed teachings, I think the drama would have been distributed over many smaller moments of insight.

Buddhism is a practice tradition. It aims at achieving the cardinal skills of virtue, wisdom, and maturity. The awakened person has perfected these skills, much as the master chef and the virtuoso pianist have perfected theirs. The Dharma is a guide for Buddhist practice, much as a cookbook is a guide for haute cuisine.

Buddhism is a practice tradition. It aims at achieving the cardinal skills of virtue, wisdom, and maturity. The awakened person has perfected these skills, much as the master chef and the virtuoso pianist have perfected theirs. The Dharma is a guide for Buddhist practice, much as a cookbook is a guide for haute cuisine. Rethinking Satipaṭṭhāna is a thoroughgoing reevaluation of the early satipaṭṭhāna teachings that integrates right view, right recollection and right samādhi based on a critical rereading of the earliest Buddhist texts in an effort to recover a doctrinally coherent, cognitively realistic, etymologically sound, functional, and explanatory interpretation of this ancient wisdom practice.

Rethinking Satipaṭṭhāna is a thoroughgoing reevaluation of the early satipaṭṭhāna teachings that integrates right view, right recollection and right samādhi based on a critical rereading of the earliest Buddhist texts in an effort to recover a doctrinally coherent, cognitively realistic, etymologically sound, functional, and explanatory interpretation of this ancient wisdom practice.